‘RIPE’ Revisited:

Inside the Making of Skavoovie & The Epitones’ Classic 1997 Sophomore Album

By Kenneth Partridge

There is absolutely nothing wrong with the first Skavoovie & the Epitones album, 1995’s Fat Footin’, a batch of bright, zippy ska groovers indebted to ’60s Jamaica, big-band jazz, and the oddball cartoons and comics that most of the band’s young members were known to devour. Fat Footin’ became the fastest-selling debut in the history of Moon Ska Records, the most important ska label of the ’90s, and nearly three decades later, it remains as refreshing a sonic cocktail as ever. Spin “Nut Monkey” next time you’re bummed and try not to smile.

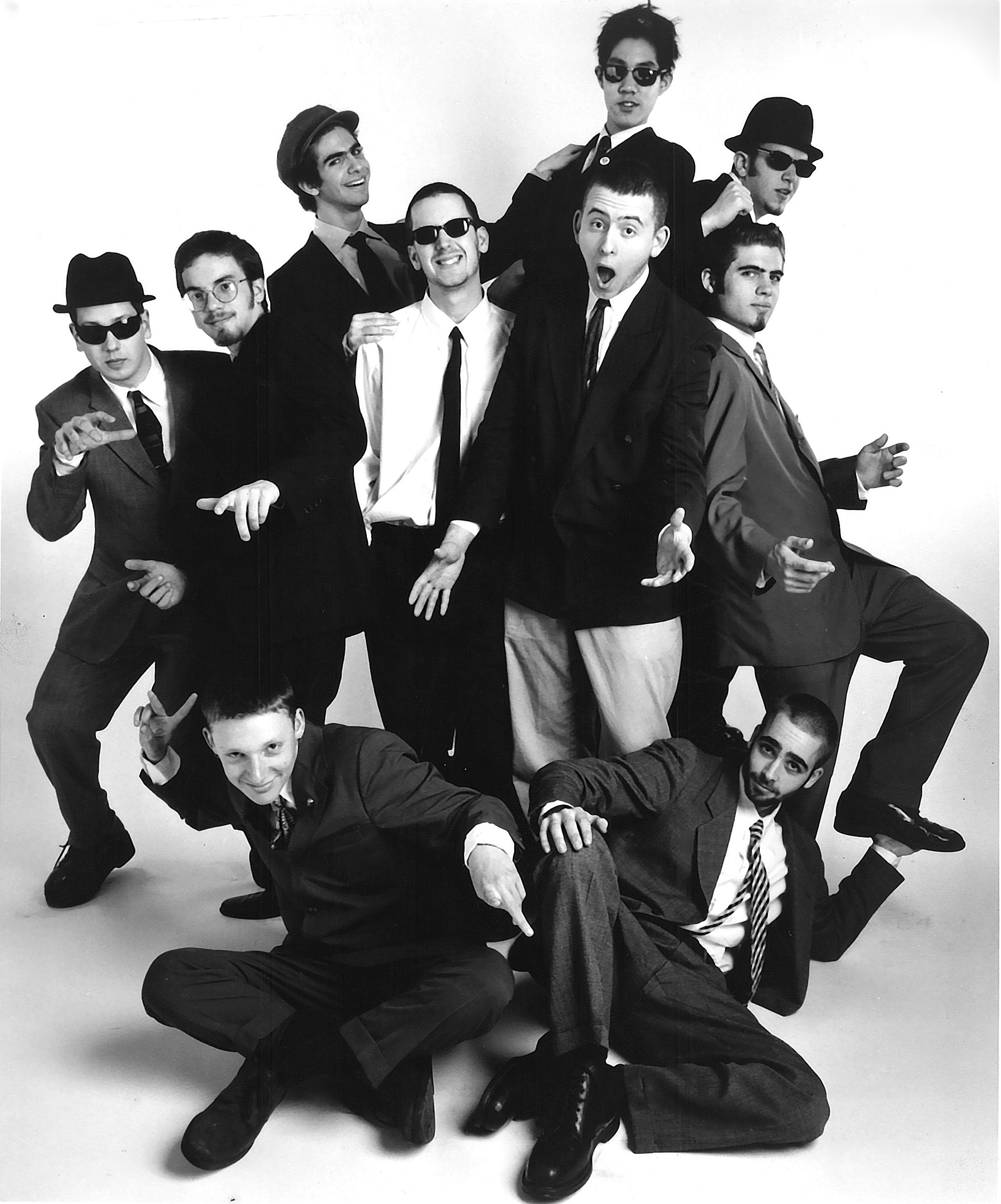

And yet Skavoovie’s real triumph came with 1997’s RIPE, a deeper embrace of the group’s comic book and sci-fi aesthetics that was naturally abetted by sharper songwriting, headier arrangements, and a fortuitous choice of producer. Less a hard left turn than an amplification of everything the 10-piece from Newton, Massachusetts, had always been about, RIPE represents a creative peak for ’90s ska. Today, after decades in digital limbo, this cult classic finally arrives on Bandcamp, with streaming services to follow. This alongside news that Skavoovie will reunite for the first time since 2000 to play the Supernova International Ska Festival in September 2024.

“If I had to describe the sound of the RIPE album as a physical manifestation, it would be Ans’ bedroom/drawing room in 1996,” says Skavoovie drummer Ben Herson. He’s talking about lead singer Ansis Puriņš, the cartoonist and illustrator who co-founded Skavoovie in 1992 at Newton South High School. Among those recruited for the band were Purins’ long-time buddies Ben Jaffe (tenor saxophone) and Jesse Farber (trumpet), fellow visual artists with similar pop-culture obsessions.

“Before we even formed the band, we would rent dumb ’40s cartoons and go see animation festivals together or some anime showing in town,” says Purins. “We all did a lot of drawing on the bus, filling several sketchbooks, and most of them are not safe for work in the least.”

Skavoovie’s lineup also included Herson, Eric Jalbert on trumpet, Joe Wensink on euphonium, Eugene Cho on keyboards, Jon Natchez on alto sax, Rob Jost on bass, and Kevin Micka on guitar. While most ska bands in the early ’90s were either fusing the music with gnashing punk rock or rehashing the 2 Tone bounce of The Specials, Skavoovie played with genuine reverence for the genre’s Jamaican roots. At the same time, they stopped short of purism and let their own kooky personalities shine through.

By the time they were getting ready to record RIPE, Skavoovie had released a demo cassette and a proper album; landed songs on popular ska compilations, such as Moon’s era-defining two-disc set Skarmageddon; and toured across the country, despite the fact everyone had gone off to different colleges. The friendships forged in childhood had grown deeper, and that came through in the new material they were writing.

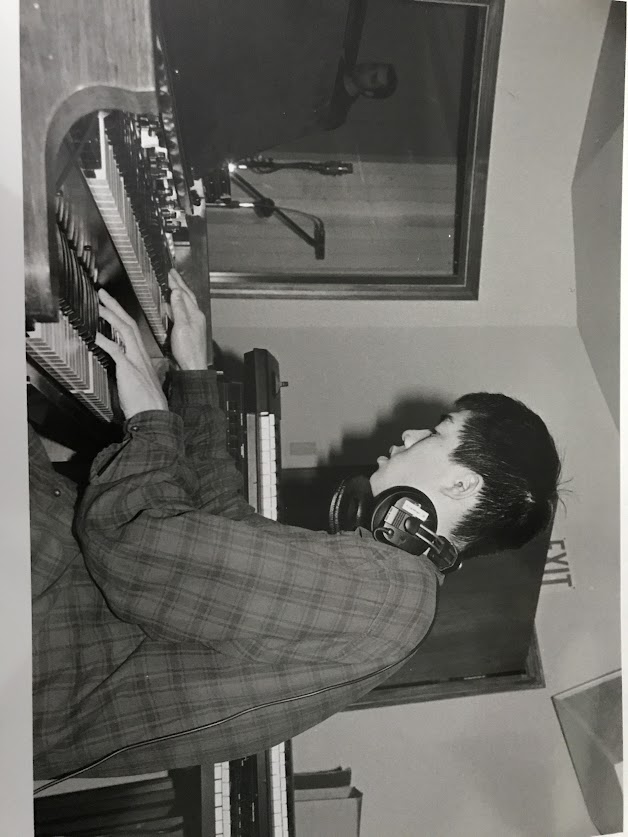

“We were family,” says Eugene Cho. “Everything was totally organic. We had space to do almost anything musically, but we developed a kind of unspoken musical identity heavily inspired by The Skatalites first and foremost. We spent a lot of nights watching this video of The Skatalites live in 1990 that Ans had on VHS, which was sort of biblical for us.”

They looked to build on that identity with RIPE, which came together at Fort Apache Studios, the legendary Boston facility where everyone from Pixies and Dinosaur Jr. to Beantown ska-core ambassadors The Mighty Mighty Bosstones had recorded some of their finest albums. According to Cho, Skavoovie’s pie-in-the-sky list of prospective producers included Elvis Costello and Jerry Dammers. A more realistic choice wound up being Victor Rice, upright bassist for Long Island trad-ska heroes The Scofflaws.

Rice had recently begun producing ska records, and his resume already included The Pietasters’ 1995 insta-classic Oolooloo and The Slackers’ hugely promising 1996 debut, Better Late Than Never. Skavoovie loved The Scofflaws, and they knew Rice had the sensibility they were looking for.

“I don’t know if bringing Victor on board was my idea, but I certainly championed it once the idea was spoken,” says Jost. “His bass sound was my true north from the moment I heard it, and I am still influenced today.”

Jost also knew Rice to be a generous soul. Right before a Skavoovie show at the New York City club Wetlands in 1995, someone broke into Jost’s car and stole his bass. The next day, Rice called Jost at his New York University dorm room and invited him to his apartment uptown. Not only did Rice make him dinner, but he gave him a ’64 Fender Precision bass on indefinite loan.

The admiration went both ways. Before taking the RIPE assignment, Rice had seen Skavoovie live, and he was impressed that a bunch of young bucks were playing with such passion and precision. Once they convened at Fort Apache, Rice was equally blown away by everyone’s good moods and positive attitudes—especially since Skavoovie had just finished a month of touring.

“What was so cool about making [RIPE] is everyone was very serious but not like jerk serious,” Rice says. “They were serious about what they were going to do. That didn’t mean they were dark or brooding. No drama. It was all good fun. It was pretty light the whole time.”

During their time on the road, Skavoovie had tightened up the new material, and as a result, they were able to take advantage of a crucial “recording formula” that Rice figured out somewhere along the way.

“When it comes to making records, you can spend 10 days in an affordable studio, and it will sound OK—or you can spend five days in an expensive studio for the same money, and it will sound better,” Rice says. “But in order to make that work, you have to show up rehearsed. You can’t be creating in the studio as much as reproducing what you’ve already created. So these guys came in totally ready to play live—everything. And it was damn near perfect. Hardly any overdubs happened on the session, because they were so totally prepared.”

Joining Rice in the studio that stress-free week was veteran British engineer Matt Ellard, who’d regale the Skavoovie crew with stories about his various A-list clients. When Jon Natchez asked Ellard to name the best musician he’d ever worked with, Ellard stunned everyone by replying, “George Michael.” Ellard presumably also dug Motörhead—there was a pair of steer horns given to him by Lemmy Kilmister hanging over the studio door.

The RIPE sessions came at a curious moment for ska, as the genre was enjoying mainstream acceptance after years on the periphery. The Bosstones, No Doubt, Rancid, and Goldfinger were regulars on MTV and alt-rock radio, and it wasn’t out of the question for a band as good as Skavoovie to dream of similar exposure. But that was never their motivation.

“While it was fun to dream, no one ever thought we’d actually ‘make it big’ like some of the more pop-driven ska bands,” says Wensink. “Sure, we enjoyed a dose of pop every now and again, but our tastes and influences were all over the map. All 10 of us were actively writing songs and collaborating, and that diversity kept the music fresh, continually evolving. That, more than any dreams of ‘making it,’ was the glue that kept us together.”

That focus on perpetual artistic growth is apparent from RIPE’s leadoff track, “Japanese Robot,” a Cho-penned instrumental that begins with a monstrous howl that only the nerdiest fans might recognize. It’s the sound of Biollante, the mutated plant-hybrid monster, sampled from the Super Nintendo game Super Godzilla, and that’s fitting, given that the song was inspired by the robot-centric work of famed Japanese manga artist Go Nagai. “Japanese Robot” is full of vaguely radar-like retro-futuristic keyboard blips and horn lines reminiscent of Saturday morning cartoons. Already, this is a very different kind of ska record.

The vibe immediately shifts on the next track, “Blood Red Sky,” the closest thing Skavoovie ever had to a hit. Swank and sinister, with just a twinge of retro-swing, it’s the noirish tale of a mysterious “Fat Man” who orders the narrator to commit a murder for reasons unknown. The wonderfully dark and hallucinatory music video appeared once on the short-lived MTV series Indie Outing, hosted by Janeane Garofalo, but that’s as far as it went.

While some hear the song and picture pinstriped ’40s-era gangsters, Herson was moved to write “Blood Red Sky” after many a harrowing night piloting the Skavoovie van through rural America under the influence of Mountain Dew.

“We were driving through these dusty, small towns that were unlike anything I had ever experienced before,” Herson says. “The lyrics unfolded as a work of fiction of what I imagined might be happening in these small desert towns. It definitely has more in common with No Country for Old Men than it does with The Untouchables, though it wasn’t influenced by either.”

Although Herson is the credited writer on “Blood Red Sky,” he got a transcription assist from Jost, who knew the nocturnal feel his bandmate was trying to capture.

“As a frequent ‘stay-up guy’ during these late-night drives, I felt dialed in to the horn lines and rhythms that Benny had asked me to help write down for the band,” Jost says. “Benny had this whole arrangement in his head, and it was a privilege to help put it on paper.”

It’s back to the world of cartoons for the next song, the superhero lark “Aquaman,” which is followed by “Frog Spirit,” a murky, lurching reggae tune inspired by Purins’ struggles with household chores as a kid. Recurring throughout “Frog Spirit” is an otherworldly gurgle-ribbit keyboard sound—kind of a “weeeOWWWW,” as Farber the trumpeter describes it—and a pulsating low-end throb created by Rice crouching on the floor and manually turning the knob of an effects pedal linked to Jost’s bass.

“Victor’s presence was such an example of what a great producer can do,” Jost says. “He exuded tranquility in this way that allowed all of us to relax into our best performances.”

Not everything on RIPE is quite so outré. The giddy Duke Ellington cover “Bli-Blip,” the solo-packed original “Hob-Nobbin’,” and the straight-up dance party “Phobus” are closer in spirit to the previous album. But even those numbers reveal an increased level of musical sophistication that was partially a response to some criticism Skavoovie had received early on. Reviewing Fat Footin’ for his respected Ska-tastrophe zine, writer Jamie Bogner knocked Skavoovie’s five-piece horn section for generally playing in unison instead of interweaving lines in more compelling ways.

“We hadn’t really gotten this kind of feedback before,” says Farber. “But I would say we responded admirably: We took it to heart, realized he was right, and made a conscious effort with our next songs to begin exploring more how we could break up the horns into different voices to enrich the sound.”

Drum dorks will appreciate the story behind the glorious snare sound essential to RIPE songs like “Wildfire” (inspired by the 1917 Western novel of the same name) and “The Plague.” On a tour prior to the RIPE sessions, Skavoovie were cruising through Ohio en route to Kentucky, where they planned to stop at KFC, naturally. At some point, the snare drum from Herson’s Pearl Maxwin kit flew off the roof and landed in a cornfield. A kindly farmer eventually mailed it back (there was a sticker on it with Herson’s name and address), but by that time, Herson had switched to a metal Ludwig snare, a far superior piece of equipment.

“Even after the farmer returned mine, I started using the Ludwig instead,” Herson recalls. “RIPE was the first recording where I used this new snare, and it sounded great. I tuned it really high, and it had a killer timbale-like sound.”

Wensink wrote RIPE’s prettiest song, “Latvian Lullaby,” though Purins jokingly demands a production credit, since he suggested the “pensive” extra bar break in the song, and since he’s actually Latvian. Listening to the tune is like flipping through a family album and letting bittersweet nostalgia wash over you like waves from the Baltic Sea.

For such a forward-looking album, RIPE ends somewhat surprisingly with “Riverboat,” one of Skavoovie’s earliest original compositions. Its existence predates even the 1994 cassette An Evening With Skavoovie. But the updated version offers further proof of how much the group had progressed in just four years together.

“The original version was a cool showcase for Eugene’s skills on the vibraphone, though it was a bitch to carry that thing around,” Farber says. “But it sometimes dragged a bit. We dropped the song for a while, maybe even a year or two. When it returned, it had evolved rhythmically, from slow traditional ska to energetic reggae.”

Skavoovie celebrated RIPE’s release via Moon Ska in May 1997 with a scorcher of a show at the Paradise Rock Club in Boston. (Present for this gig were guitarist Daniel Neely and trumpeter Ben Lewis, who’d replaced Micka and Jalbert before the album was released.) Looking back, Cho remembers it being an “incredible time for ska,” though not necessarily because of all that aforementioned major-label interest. There was a genuine youth movement happening across the country.

“RIPE was one of the first major releases made by kids that were the same age as most of the fans,” Cho says. “There was a very direct connection. Unlike the kings of the N.Y., L.A., or Boston scenes in the late ’80s to early ’90s, who were in their late 20s or 30s, it was all just fucking kids playing for other kids. There were a ton of college and high school bands that we would play with everywhere headlining large venues, and it was amazing to be part of that.”

This thriving scene couldn’t last forever. In the two years following RIPE’s release, ska became very uncool very quickly, and the shows got smaller and smaller. With nothing to lose, Skavoovie moved in together and dedicated themselves to writing and recording a third album. Aiming to push past genre limitations, they leaned more heavily into their bizarro jazz tendencies and came up with 1999’s exuberant and experimental The Growler, which sadly arrived to little fanfare. The following year, Skavoovie played their final show on a crummy outdoor stage at Yale University.

“There was what looked like a 13-year-old kid doing the sound,” Purins remembers. “I was covered in poison ivy. There were almost 12 people there. I think we did the gig because we still owed our manager and our booking agent money. We all maybe wanted a final show, but it wasn’t meant to be this. We never officially broke up. We just all kind of felt it and knew it was over.”

The unceremonious ending wasn’t enough to kill the band’s friendships. Team Skavoovie remained tight into the new century, and during the pandemic, they began chatting regularly on Zoom. That was the impetus for the long-overdue digital release of their back catalog (Fat Footin’ hit the streamers last year), and it led to the upcoming reunion at Supernova, which celebrates its 10th anniversary in 2024.

“We’ve had offers to tour South America, Europe, and lots of festivals, but nobody could figure out how to assemble us all,” says Purins. “Thanks to Tim and April [Receveur] from Supernova for making it so easy. We are all really, really excited to play again. I wish I could share the set list with you all. Fans can expect all original members of classic Skavoovie to perform. You can expect us to finally look like men in suits and not like little kids at a wedding.”

And fans might even have cause to expect a little more.

“There is an incredible amount of unreleased live music and some lost tracks that were never released,” Purins says. “I happen to know for a fact Benny and Rob are working on a slamming new tune that sounds like an ’80s Jamaican pro wrestling match between Duke Reid and Hulk Hogan.”